Entrepreneurship

and Work in a Post-Fordist Organization: the Case of an

Italian Industrial District

1. Different patterns of

organization

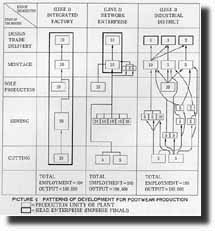

In order to introduce you to the

transformation of work and participation that has taken

place in the North East of Italy, I think it’s best

to start with a simple diagram. This describes the

footwear production process (picture 1 - Patterns of

development in footwear production). In order to introduce you to the

transformation of work and participation that has taken

place in the North East of Italy, I think it’s best

to start with a simple diagram. This describes the

footwear production process (picture 1 - Patterns of

development in footwear production).

In Italy three different

kinds of organization may be found within a single

technical process (in this case, footwear).

Each of the three production

methods shown in the diagram produces the same

product (or family of products), has the same technology,

the same number of employees with identical skills, the

same output at the end of the process (and also at any

single stage of the process) and the same standard of

productivity, cost and wage distribution.

The most important

difference concerns the social agreement: the degree of

participation in capital investment and income

distribution.

In the first pattern (the

integrated firm or fordist organization), market

analysis, decision making, profit and capital investment

are highly concentrated in one head office at the top of

the value chain. Workers and bosses just attend to the

top manager’s decisions and behave in relation to a

contract formally sanctioning a low level of

participation further down the chain in those stages of

the process that are far from the final market line.

In the third pattern,

though, (the industrial district or post-fordist

organization) market analysis, product design, decision

making, profit and investment are shared among a wide

number of entrepreneurs.

In the other pattern of

organization (the network enterprise) all these functions

are performed by quasi-entrepreneurs (exclusive

sub-contractors for one head enterprise), in a mixture of

market and hierarchy (in this case participation of

sub-contractors in the general strategy of the chain is

limited to technical choices).

In the last decade the non-fordist

mode of production has become predominant in North East

Italy mainly for two reasons:

- it is suited to

globalization, more flexible in the face of market

failure, and able to promote a team game among

entrepreneurs and workers at different levels, ensuring

quicker innovation along the line, reducing risks, time

to market and the cost of re-shaping the system in the

event of external shocks;

- large amounts of capital

are not required for each participant in the value chain

to follow a successful path of development.

2. Why have post-fordist

modes of production taken the leadership in Italy ?

The first organization

seems rigid in the face of external shocks and unable, in

Italy, to shift toward lean production or any other kind

of risk-sharing social agreement.

In this mode of production

a market failure affects the structure as a whole, with

high costs in re-allocating human resources and capital

goods. If the top manager fails in market forecasts and

loses part of his market share to other competitors, the

company as a whole goes bankrupt and employees and

machinery have to be transferred elsewhere, with high

economic and social costs.

On the contrary, the

network enterprise and the industrial district have a

capacity to absorb external shocks without evident costs.

If the failure is the result of a mistake committed by

the top manager of one of the district head enterprises,

the only consequence to industrial suppliers (independent

sub-contractors in this case) is their need to change the

destination of their output. The industrial section of

the chain is not affected by external shocks and its

members are simply forced to shift from the failing head

enterprise to another, quickly joining the winning team.

A fordist organization,

however, can be established only with the help of big

banks or by wealthy families. The total amount of capital

needed to develop a new integrated company is high, while

total profit is concentrated in very few hands.

In the post-fordist

organization, on the other hand, each entrepreneur has to

invest only what is required at his own stage of the

process: it is easier for him to find the money, or a

bank to provide a small loan. Meanwhile the total profits

are shared among a large number of stock and stake

holders.

Italy is a country

typified by small banks and family capital. A

post-fordist organization (in which risk, investment and

profit are shared among a lot of people) is more than an

opportunity, it is a compulsory course of development.

3. The rising of a new

kind of entrepreneurship and work

We here briefly describe

the rise of a new participative game in Italy: small

entrepreneurs and skilled workers continuously shifting

from one chain to another, from one job to another,

concerned only with joining the winning team.

Of course this is possible

only in a local context (the atmosphere of a district)

that allows anyone to shift without dramatic changes in

habits, friends, home, culture, etc., and this is

possible only where the territory plays the special role

of a good social integrator.

The local district, a term

identifying the territory where a community of people and

a population of small firms join together (see F.Pyke,

W.Sengenberger, F.Cossentino or G.Becattini by

ILO-Geneva, 1991 and 1997, or P.Krugman’s "Geography

and Trade", 1991), is the environment in which a

new kind of entrepreneurship and work can take off.

A small businessmen is,

first of all, a member of the community and part of a

team (not of a social class). He knows that his success

depends on cooperation more than on competition, and for

this reason he participates in local institutions and

associations.

Workers also feel they

belong to a system, not to a single company. They look at

their own career as being the first step in a possible

entrepreneurial upgrading process that starts with

sub-contracting and carries on to head enterprise.

When we say workers in

North East Italy we mean skilled workers. Skilled

(and affluent) workers are a large part of the

work force because of the prevalence of traditional

sectors and the technical structure of the process which

is still oriented towards custom-made products and a high

level of customer service.

In this context, learning

by doing is the standard way of improving human

resources. But the ability to bargain individual

know-how within the factory and in the territory is

also an important part of the learning process.

4. What, then, is

participation in these organizations we refer to as post-fordist

(non-fordist) organizations ?

Although entrepreneurs

believe in free market laws, individual interest and so

on, and though they represent a single stage of the

process (as sub-contractors), they naturally tend to

cooperate in the final success of the chain.

In order to survive (as

entrepreneurs) they are forced to understand, anticipate

and influence the strategy of head companies; they must

participate in the collective shift of the district

towards a new challenge and use competition and

cooperation as non-alternative means of growth.

Participation in this case

is compulsory: an entrepreneur must take part in the

collective game of the district or he may be pushed out

and suffer social downgrading.

Up-grading and downgrading

have no apparent consequences on the economic condition

of people living in a district (there are no startling

income differences between a small owner with 5 to 10

workers, a single handed entrepreneur and a

skilled worker), but being identified as a loser

may have dramatic consequences (emigration).

Workers, on the other

hand, have a special opportunity on the district labor

market: in a territory with hundreds of firms performing

similar tasks, using similar machinery and techniques,

and continually searching for new ideas and skills, they

can choose their company.

The local labor market in

a district is a perfect labor market (at least for

skilled workers, but also offering good chances to

others).

In this case participation

comes from the awareness that a worker can control part

of the output and measure the improvement of his own

professional skills. Every day a worker can measure the

value of his own personal capital, and participate in the

design of new products and the re-shaping of the work

process.

These special conditions

are currently attracting worldwide interest in the

Italian pattern of development and its economic and

social success. They may represent the rise of a new

pattern of development or what someone has recently

called "The End of Work" (Rifkin).

Paolo Gurisatti

|